I know the notion of “food vs. fuel,” or the economic impact of using grains – mainly corn – to make ethanol is controversial. Lester Brown of the Earth Policy Institute – a source I trust implicitly – has argued forcefully that using food crops for fuel increases food prices. At least one of our friends over at Gas 2 has taken the opposing position. I don’t want to enter this one – I’m not knowledgeable enough on the topic – but I think it’s safe to say that finding a reliable, economic feedstock for ethanol that’s not a food crop would be a genuine step forward.

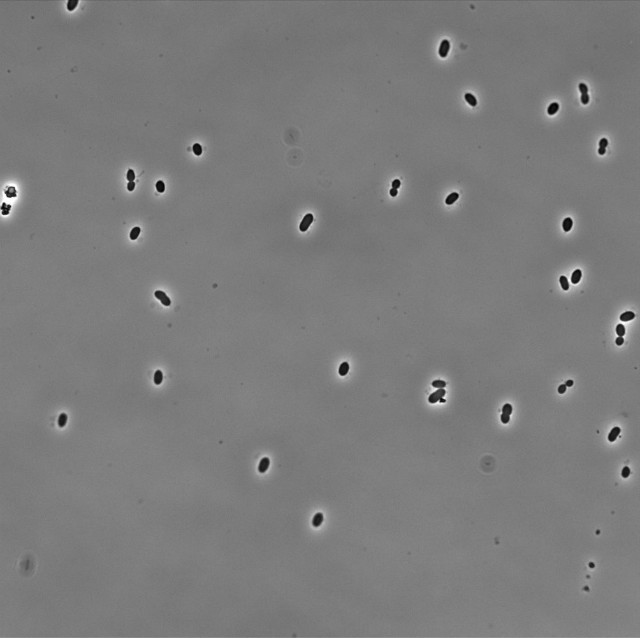

For years, cellulosic ethanol made from crops like switchgrass (which can grow on marginal land) or agricultural waste has held promise on this front… though it also presents a number of challenges that have prevented producers from efficiently scaling up its production. Now, researchers at Indiana University believe they’ve discovered one way to cut some of that cost. According to the Christian Science Monitor, the bacterium Zymomonas mobilis (pictured above) could serve as an ideal fermentation agent for cellulosic ethanol for a number of reasons, including their discovery that it can feed on nitrogen gas:

…it also converts biomass such as switch grass and crop residues into ethanol faster and in larger quantities, cell for cell, than does yeast, the most widely used fermenting agent. It leaves less bacterial biomass at the end of the process. And it carries something yeast doesn’t – an enzyme that gives it an ability to draw the nitrogen it needs as fertilizer directly from air, rather than from costly commercial supplements.

While this isn’t a total game-changer – there are still challenges to overcome – it’s significant:

[IU researchers] estimated that using N2 gas, which can be produced on-site at production facilities, in place of costly nitrogen supplements could save an ethanol production facility over $1 million dollars a year. Using N2 gas could also have environmental benefits such as avoiding carbon dioxide emissions associated with producing and transporting the industrial fertilizers.

So, a definite step forward in developing non-food sources of ethanol. One question that came to me: how would shifting crop waste to ethanol affect no-till farming methods which rely, in part, on leaving agricultural waste on the ground to break down and add carbon to the soil. Or is there enough to go around? If you know more about this than I do, please chime in…

Image credit: IU Bloomington Newsroom