When it comes to respectability and clout in the realm of progressive advocacy, John Robbins ranks pretty high on almost all fronts. The author of The Food Revolution, Diet for a New America, and other books, Robbins is the son of BaskinRobbins co-founder Irv Robbins who took a very different path than many corporate heirs. Instead of pushing a corporate agenda with every ice cream cone, Robbins is an energetic and prolific voice for a healthier, more humane, more sustainable world. He is the recipient of the Rachel Carson Award, the Albert Schweitzer Humanitarian Award, the Peace Abbey’s Courage of Conscience Award, and lifetime achievement awards from groups including Green America.

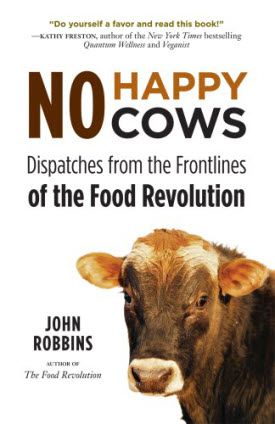

Obviously, then, Robbins has taken on the status of expert on issues ranging from human health, to environment, to animal welfare, to a fulfilling life, and beyond. His newest book, No Happy Cows: Dispatches from the Frontlines of the Food Revolution, is a testimonial to this fact. As its title implies, the book is a collection of blog posts, articles, and new essays on a broad range of topics, all centered on the issue of human wellness in a morbidly unsustainable modern world.

Beginning from the premise that human wellness (physical, emotional, spiritual) is tied up closely with the well-being of the planet and its other inhabitants, Robbins waxes philosophical (and polemical) in chapters of varying length, divided into four parts: “Caring for Creatures” (farmed-animal welfare), “What Are We Putting into Our Bodies?” (human health and dietary choices), “Industrial Food Production—and Other Dirty Dealings” (the harmful effects of industrialized food systems), and “Being Human in This Troubled World” (how to sustain oneself and engage in the world).

At its best, No Happy Cows offers a primer on some of the most pressing aspects of human, social, and planetary health, and in doing so makes a case for how intimately connected these separate spheres are—that they are, in fact, not separate at all. The health of one depends on, and in turn supports, the health of them all.

That said, No Happy Cows is quite clearly a “human interest” book, in that its primary concern and lens through which to view the world is a human one. With Robbins’ obviously extensive reflection and training in compassionate living, this makes for a book brimming with messages of respect, cherishing dignity, avoiding judgment and ridicule, and seeking a mindfulness of perception and response to all situations, no matter how grave. “To me this is grace,” he writes, “to have the veils lifted from our eyes so that we can recognize and serve the goodness in each other” (16).

As a result of this mindset, Robbins is skillful in tackling a host of difficult and touchy subjects, which are at the same time in dire need of attention—and action—if we have any hope of building a healthy, sustainable world: factory farming of various animals, the healthfulness (or not) of soy and chocolate, antibiotics and growth hormones in animal products, the importance of buying fair trade, peddling junk food to kids, and the ups and downs of human relationships.

I appreciated No Happy Cows for its overwhelming tone of compassion, and for the fact that it may well serve as the first introduction for many readers to one or more of the topics that Robbins covers. It is, after all, a collection of “dispatches,” not a tightly knit and precisely structured argument.

At the same time, though, there are some critical shortcomings of No Happy Cows and Robbins’s approach to advocating “wellness” that deserve attention.

By far the biggest blind spot in Robbins’s vision, I think, is the very same humanitarian (or humanistic) ethic that underlies his concern for compassion and dignity. Robbins repeatedly advocates making better food choices, eating a “plant-strong” diet, and avoiding the worst of industrialized animal-based and junk foods. However, following his advice, a person could easily continue eating foods that entail cruelty, exploitation, and harmful health effects on themselves, animals, and the planet.

Robbins, in truth, takes on the worst of industrial animal agriculture and corporate manipulation of consumers, whether that be feedlot cattle, hormone- and antibiotic-riddled dairy cows, or crate-bound pigs. However, he fails to explore or adequately acknowledge the equally harmful and cruel practices involved with all animal agriculture—artificial insemination, killing male chicks of laying hens, continual impregnation of dairy cows, removing and confining the male calves of dairy cows, and even (especially) the negative impacts on human and planetary health that even “humanely raised” animal products can have. That is, he fails to acknowledge that, looked at in full honesty and with more than human interest, there truly are no happy cows in animal agriculture.

This oversight in No Happy Cows is understandable given Robbins’s emphasis on tolerance and compassion towards humans. He says in one essay, “I draw strength from my kinship with animals. Some of my best friends have four legs” (170). And yet the entire fourth part of the book is on human-to-human relationships, and dealing with the suffering of humans as they struggle with challenges to health, happiness, and prosperity. The flaw, then, is that Robbins is ultimately too tolerant of lifestyle choices that are, though not as bad as most modern lifestyles, still demonstrably unsustainable.

This oversight in No Happy Cows is understandable given Robbins’s emphasis on tolerance and compassion towards humans. He says in one essay, “I draw strength from my kinship with animals. Some of my best friends have four legs” (170). And yet the entire fourth part of the book is on human-to-human relationships, and dealing with the suffering of humans as they struggle with challenges to health, happiness, and prosperity. The flaw, then, is that Robbins is ultimately too tolerant of lifestyle choices that are, though not as bad as most modern lifestyles, still demonstrably unsustainable.

The implication, then, is that Robbins has not divested himself of the belief that human wellness takes priority over the welfare and interests of other animals. His recommendations of a “plant-strong” diet and personal choice of a vegetarian (not vegan) diet lose their moral strength when one recognizes that the case he makes for them is an even better case to go vegan. That is, he takes the easy, and more popular or acceptable, approach of practicable compromise instead of laying out a consistent and clear plan for transitioning to a truly compassionate, healthful, animal-free lifestyle. And his unwillingness to pursue his own arguments to their logical (and necessary) conclusion is both significant and common in many books on diet, health, and environment, based on an assumption that people either cannot tolerate, cannot understand, or cannot achieve a complete break from an industrial system that places animals in the position of commodities.

Consequently, we see Robbins providing options for purchasing “safe” dairy products, or giving advice for finding truly “humane” eggs, but not any discussion about going from “plant strong” to animal free. There is little recognition that vegan diets (and lifestyles) accomplish all of the goals he seeks to achieve, and more. Perhaps this is because vegans are still popularly perceived as rigid, marginal, or fanatical (so often Robbins qualifies some point with “you don’t have to be an animal rights activist to see…”). Or perhaps it is the idea that vegan diets are too difficult for most Americans.

Whatever the case, No Happy Cows suffers the most from not giving due diligence to the premise of the title: that there are in fact no happy cows, or any other animals (including people), in the modern industrial food complex. Although that sort of a program and argument would have made for a very different book, I was greatly disappointed to see so little attention given to the promotion of vegan lifestyles as part of an overall compassionate, sustainable human existence.

No Happy Cows serves as a great starting point for learning about some of the many ways in which our society generates suffering, and for many readers it may open their eyes to one or more cruel practices tied up in the food they eat. But if readers stop where the author stopped, and do not give as much respect to non-human animals as they do to humans (including themselves), then we will fall short of creating the compassionate, enduring planet that Robbins so passionately advocates.

Top image credit: Martin Gommel via photopin cc