By Lester R. Brown

In 1994, I wrote an article in World Watch magazine entitled “Who Will Feed China?” that was later expanded into a book of the same title. When the article was published in late August, the press conference generated only moderate coverage. But when it was reprinted that weekend on the front of the Washington Post’s Outlook section with the title “How China Could Starve the World,” it unleashed a political firestorm in Beijing.

The response began with a press conference at the Ministry of Agriculture on Monday morning, where Deputy Minister Wan Baorui denounced the study. Advancing technology, he said, would enable the Chinese people to feed themselves. This was followed by a government-orchestrated stream of articles that challenged my findings.

The strong reaction surprised me. In retrospect, although I had followed closely the Great Famine of 1959–61, during which some 30 million people starved to death, I had not fully appreciated the psychological scars it left. The leaders in Beijing are survivors of that famine. As a result of that traumatic experience, no leader could acknowledge that China might one day have to import much of its food. China, they said, had always fed itself, and it always would.

How China Tried to Become Grain Self-Sufficient

As party leaders assessed the situation, they decided to launch an all-out effort to maintain grain self-sufficiency. The government quickly adopted several key production-boosting measures, including a 40 percent rise in the grain support price paid to farmers, an increase in agricultural credit, and heavy investment in developing higher-yielding strains of wheat, rice, and corn, their leading crops.

They offset cropland losses in the fast-industrializing coastal provinces by plowing grasslands in the northwestern provinces, a measure that contributed to the emergence of the country’s massive dust bowl. In addition to overplowing, they expanded irrigation by overpumping aquifers.

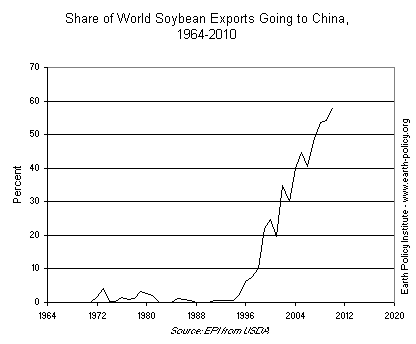

Lastly, the Party made a conscious decision to abandon self-sufficiency in soybeans and concentrate their agricultural resources on remaining self-sufficient in grain. The effect of neglecting the soybean in the country where it originated was dramatic. In 1995 China produced and consumed nearly 14 million tons of soybeans. In 2010 it was still producing only 14 million tons—but it consumed nearly 70 million tons, most of it to supplement grain in livestock and poultry rations. China now imports four-fifths of its soybeans. (See data.)

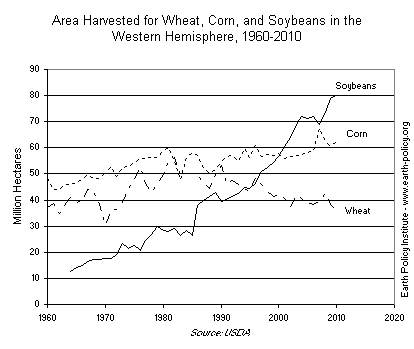

China’s decision to import vast quantities of soybeans led to a restructuring of agriculture in the western hemisphere, the only region that could respond to such a massive demand. The United States now has more land in soybeans than in wheat. Brazil has more land in soybeans than in all grains combined. Argentina, with twice as much land in soybeans as in grain, is fast becoming a soybean monoculture. For the hemisphere as a whole, there is now more land in soybeans than in either wheat or corn.

The United States, Brazil, and Argentina—the big three soybean producers—now account for more than 80 percent of the world harvest and nearly 90 percent of soybean exports. Nearly 60 percent of world soybean exports go to China.

What is the environmental and economic impact of China’s grain demand?

Deborah Dolen

China cannot feed China. Great article!

lark

Great article except that point that America will be hostage to China because of the need to sell Treasuries. Not so. Their purchase per cent is down to 40% and falling. Treasuries find buyers in this uncertain world. China is only in the Treasury market to enforce a currency peg. They are not doing this in the spirit of friendship.