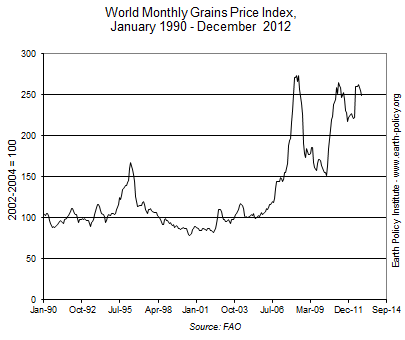

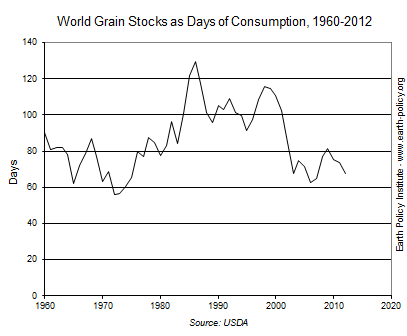

Global grain consumption has exceeded production in 8 of the last 13 years, leading to a drawdown in reserves. Worldwide, carryover grain stocks—the amount left in the bin when the new harvest begins—stand at 423 million tons, enough to cover 68 days of consumption. This is just 6 days more than the low that preceded the 2007–08 grain crisis, when several countries restricted exports and food riots broke out in dozens of countries because of the spike in prices.

Grain prices receded somewhat during the recent recession, only to jump again in 2010 when heat and drought withered wheat in Russia, prompting an export ban. The poor prospects for the 2012 harvest led to the third spike in world market prices in just six years. This time around, even with its 2012 harvest forecast to be smaller than in 2010, Russia announced that it would avoid suspending exports.

Following a record high year in 2011, global grain trade in 2012 dropped back to 2010 levels. The 296 million tons of traded grain made up 13 percent of global consumption. Japan remained the world’s largest importer, taking in a net 24 million tons (mostly corn to feed livestock and poultry), equal to 73 percent of what it used. Densely populated South Korea imported 13 million tons of grain, also amounting to 73 percent of its consumption. Feed corn dominated imports in Mexico—the cradle of corn—as well, with 15 million tons of grain imports accounting for 32 percent of its use. In the arid Middle East, Egypt took in 14 million tons of grain, largely wheat for bread, making up 39 percent of its grain consumption. Saudi Arabia’s 13 million tons of grain imports, mostly barley for feed, accounted for 87 percent of its use.

China made the list of top 10 net importers for the second year in a row, taking in 8 million tons of grain in 2012, down from 11 million tons in 2011. China’s 2012 imports (roughly split between corn, wheat, rice, and barley) amounted to just 2 percent of its domestic consumption, but the country’s recent forays into world grain markets following years of self-sufficiency have captured attention because of China’s enormous potential appetite. (Soybeans are another story; China takes in 60 percent of world soybean exports.)

Although the United States is by far the world’s largest grain exporter, its share of the world market is shrinking. The net 49 million tons of grain the United States shipped out in 2012 was its smallest outflow since 1971. U.S. corn exports of 22 million tons were less than half the quantity of five years prior and just slightly larger than outflows from each of its South American competitors, Argentina and Brazil. For rice, Thailand was edged out of its top exporter position for the first time in three decades when India unloaded stocks accumulated during a four-year ban on non-Basmati exports.

Looking forward, the 2013 winter wheat crop could be in trouble because of droughts in the United States and in the Black Sea region. And while the heart of the Corn Belt has received some precipitation since the baking summer, soil moisture remains low and could possibly hinder spring planting, further tightening the corn situation. This is bad news when strong harvests are needed to rebuild stocks and to help stabilize prices.

Another hindrance to expanding production is the leveling off of yields for a number of key crops, importantly rice in Japan and South Korea and wheat in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. It appears that farmers in some areas have maximized productivity and are now running into biological constraints. On top of that, climate change is heightening the likelihood of weather extremes, like heat waves, droughts, and flooding, that can so easily decimate harvests. Although 70 days’ worth of grain stocks once was considered enough to provide food security, a world with growing climate instability requires a larger buffer to protect against food price shocks. Skyrocketing prices hit the poorest among us the hardest, and ultimately they can spark instability that affects everyone.

For further discussion of the world food situation, see Full Planet, Empty Plates: The New Geopolitics of Food Scarcity by Lester R. Brown (New York: W.W. Norton & Co.), with data, video, and slideshows at www.earth-policy.org.

Image credit: agrilifetoday via photopin cc