Image credit: Tiago Fioreze at Wikimedia Commons under a Creative Commons license

Originally published at Plan B Updates

By Lester R. Brown

Some 3,000 years ago, farmers in eastern China domesticated the soybean. In 1765, the first soybeans were planted in North America. Today the soybean occupies more U.S. cropland than wheat. And in Brazil, where it spread even more rapidly, the soybean is invading the Amazon rainforest.

For close to two centuries after its introduction into the United States the soybean languished as a curiosity crop. Then during the 1950s, as Europe and Japan recovered from the war and as economic growth gathered momentum in the United States, the demand for meat, milk, and eggs climbed. But with little new grassland to support the expanding beef and dairy herds, farmers turned to grain to produce not only more beef and milk but also more pork, poultry, and eggs. World consumption of meat at 44 million tons in 1950 had already started the climb that would take it to 280 million tons in 2009, a sixfold rise.

This rise was partly dependent on the discovery by animal nutritionists that combining one part soybean meal with four parts grain would dramatically boost the efficiency with which livestock and poultry converted grain into animal protein. This generated a fast-growing market for soybeans from the mid-twentieth century onward. It was the soybean’s ticket to agricultural prominence, enabling soybeans to join wheat, rice, and corn as one of the world’s leading crops.

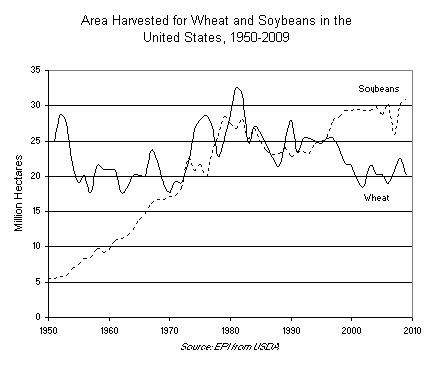

U.S. production of the soybean exploded after World War II. By 1960 it was close to triple that in China. By 1970 the United States was producing three fourths of the world’s soybeans and accounting for virtually all exports. And by 1995 the fast-expanding U.S. land area planted to soybeans had eclipsed that in wheat.

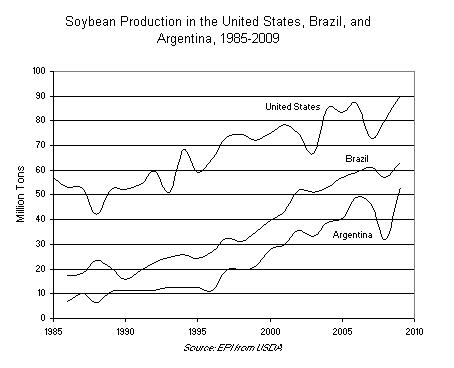

When world grain and soybean prices climbed in the mid-1970s, the United States—in an effort to curb domestic food price inflation—embargoed soybean exports. Japan, then the world’s leading importer, was soon looking for another supplier. And Brazil was looking for new crops to export. The rest is history. In 2009, the area in Brazil planted to soybeans exceeded that in all grains combined.

At about the same time the soybean gained a foothold in Argentina, where it staged the most spectacular takeover of all. Today more than twice as much land in Argentina produces soybeans as produces grain. Rarely does a single crop so dominate a country’s agriculture as the soybean does Argentina’s. Together, the United States, Brazil, and Argentina produce easily four fifths of the world’s soybean crop and account for 90 percent of the exports.

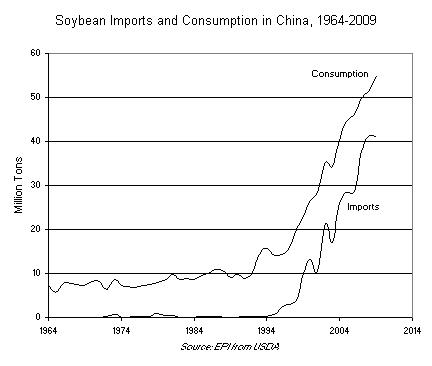

During the closing decades of the last century, Japan was the leading soybean importer, at nearly 5 million tons per year. As recently as 1995, China was essentially self-sufficient in soybeans, producing and consuming roughly 13 million tons of soybeans a year. Then the dam broke as rising incomes enabled many of China’s 1.3 billion people to move up the food chain, consuming more meat, milk, eggs, and farmed fish. By 2009 China was consuming 55 million tons of soybeans, of which 41 million tons were imported, accounting for 75 percent of its soaring consumption.

Today half of all soybean exports go to China, the country that gave the world the soybean. Soybean meal mixed with grain for animal feed made it possible for Chinese meat consumption to grow to double that in the United States.

Since 1950 the world soybean harvest has climbed from 17 million tons to 250 million tons, a gain of more than 14-fold. (See data.) This contrasts with growth in the world grain harvest of less than fourfold. Soybeans are the second-ranking U.S. crop after corn, and they totally dominate agriculture in both Brazil and Argentina.

Where does the 250-million-ton world soybean crop go? One tenth or so is consumed directly as food—tofu, meat substitutes, soy sauce, and other products. Nearly one fifth is extracted as oil, making it a leading table oil. The remainder, roughly 70 percent of the harvest, ends up as soybean meal to be consumed by livestock and poultry.

So although the soybean is everywhere, it is virtually invisible, embedded in livestock and poultry products. Most of the world harvest ends up in refrigerators in such products as milk, eggs, cheese, chicken, ham, beef, and ice cream.

Satisfying the global demand for soybeans, growing at nearly 6 million tons per year, poses a challenge. The soybean is a legume, fixing atmospheric nitrogen in the soil, which means it is not as fertilizer-responsive as, say, corn, which has a ravenous appetite for nitrogen. But because the soy plant uses a substantial fraction of its metabolic energy to fix nitrogen, it has less energy to devote to producing seed. This makes raising yields more difficult.

In contrast to the impressive gains in grain yields, scientists have had comparatively little success in raising soybean yields. Since 1950, U.S. corn yields have quadrupled while those of soybeans have barely doubled. Although the U.S. area in corn has remained essentially unchanged since 1950, the area in soybeans has expanded fivefold. (See data.) Farmers get more soybeans largely by planting more soybeans. Herein lies the dilemma: how to satisfy the continually expanding demand for soybeans without clearing so much of the Amazon rainforest that it dries out and becomes vulnerable to fire.

The Amazon is being cleared both by soybean growers and by ranchers, who are expanding Brazil’s national herd of beef cattle. Oftentimes, soybean growers buy land from cattlemen, who have cleared the land and grazed it for a few years, pushing them ever deeper into the Amazon rainforest.

The Amazon rainforest sustains one of the richest concentrations of plant and animal biological diversity in the world. It also recycles rainfall from the coastal regions to the continental interior, ensuring an adequate water supply for Brazil’s inland agriculture. And it is an enormous storehouse of carbon. Each of these three contributions is obviously of great importance. But it is the release of carbon, as deforestation progresses, that most directly affects the entire world. Continuing destruction of the Brazilian rainforest will release massive quantities of carbon into the atmosphere, helping to drive climate change.

Image credit: http://www.flickr.com/photos/16725630@N00/ / CC BY 2.0

Brazil has discussed reducing deforestation 80 percent by 2020 as part of its contribution to lowering global carbon emissions. Unfortunately, if soybean consumption continues to climb, the economic pressures to clear more land could make this difficult.

Although the deforestation is occurring within Brazil, it is the worldwide growth in demand for meat, milk, and eggs that is driving it. Put simply, saving the Amazon rainforest now depends on curbing the growth in demand for soybeans by stabilizing population worldwide as soon as possible. And for the world’s affluent population, it means moving down the food chain, eating less meat and thus lessening the growth in demand for soybeans. With food, as with energy, achieving an acceptable balance between supply and demand now means curbing growth in demand rather than just expanding supply.

Lester R. Brown is the president of the Earth Policy Institute and author of Plan B 4.0: Mobilizing to Save Civilization.

GERALDO A. LOBATO FRANCO

Way back in the 1970’s I took a Pan-Am flight from LAX to (then) RIO, with a stop in Guatemala, as I remember, its high up airport which had to be negotiated among seemingly boiling volcanoes… later that night we flew over well lit Bogotá and soon enough we were on top (perhaps at 30,000 feet) of the Amazon jungle, to my surprise also widely lit by forest fires, many of them, in large extensions.

Just a bit later, perhaps in four or five hours, we were over sleepy planewing-like Brasília… I was truly amazed by the fact that forest fires were so comparatively near main cities and soon found out that the devastation was running amok, as still is today, perhaps as local authorities now claim, with a lesser impetus of utter destruction. But destruction still goes on day and night.

Their methods of deforestation are unbelievably rude and stupid: given areas are driven in by means of large weighty iron chain, brought into scene pulled by two tractors running in parallel.

Once most vegetation is brought down, gasoline is poured into this biomass and a fire is started, some lasting several days; however, I have heard of napalm or gelatinous gasoline been used to start the biological eco-holocaust, just as simple as I am now writing and you are reading…

My questions are: does mankind need soybeans or cattle raised there, which may or may not be sold in international markets? Do local farmers or Brazilian Government know what they are doing for the future of mankind? Does humanity know what they are in the process of losing? Are we all aware of how much we are narroweing the varieties we have at our tables to eat? How are to survive the small local agricultural producers in face of huge conglomerates of everything (for instance, petro-agro-farmaceuticals, otherwise known as makers of poisonous biocidals)?

The questions are many and up to now few are the answers. Many of them should rise at the so called First World nations which, in the end are the major favoured partners o such a mess.

All owners of the Amazon forest are mere present losers. Mankind is the real loser in the end.

Alexander

This is a great article and an eye opener. I just wanted to add my perspective as an American living in the Amazon from 07-10. First, all countries should stop all imports of wood from Brazil until they can figure out a way to legitimately harvest these resources. Which by the way, is probably never. It is, I believe the biggest catalyst to deforestation. Once the land is cleared, the wood sold and the final remnants cleared to make charcoal, then the ranchers and farmers move in. During the whole process, the very government agencies set up to prevent misuse, are part of the process with paybacks for illegal permits to clear, false certifications for wood harvested and/or bribes to look the other way. 99.9% of the wood sold, is illegally harvested, but leaves with the government stamp of approval. Brazilian government certification is worthless!! Buyers feel good and have “proof” to show end users that they are responsible buyers. When in fact, they have no real way to know if it’s harvested legally or not. It is way past time for the world to wake up and realize depending on Brazil to manage the Amazon is foolhardy. It is the outside that needs to act, by boycotting Brazilian wood, meat and soy products. It might be the pressure that Brazil needs to get its house in order. You would need outsiders to verify, because as noted above, you can’t trust the government agencies responsible for this. When the big boys feel the pain, they will focus on protecting what they have instead of continuing to plunder.